Medicaid expansion took effect in 2021 due to a voter-approved ballot measure. By mid 2024, nearly 300,000 people were enrolled in expanded Medicaid.

Medicaid in Missouri is called MO HealthNet. Coverage is available to low-income children and adults, and to people with low incomes and low asset levels who are aged, blind, or disabled. The following populations are eligible for MO Health Net (note that the listed income limits include a built-in 5% income disregard added to the eligibility limits; this is used for all Medicaid eligibility based solely on income):

As of mid-2024, Missouri Medicaid is under review by federal regulators due to a lack of compliance with rules regarding application timeframes. Federal rules give states up to 45 days to process Medicaid applications, and nearly three-quarters of Missouri’s applications were taking longer than that as of early 2024. At that point, Missouri had the worst application processing delays in the country. 2

Federal poverty level calculatorof Federal Poverty Level

You can enroll through HealthCare.gov or through MO HealthNet. You can also enroll by phone at 800-318-2596.

Eligibility: Parents with dependent children are eligible with household incomes up to 18% of FPL. Children are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP with household incomes up to 300% of FPL, and pregnant women are eligible with household incomes up to 196% of FPL.

As described below, Missouri had a long and somewhat complicated road to Medicaid expansion. But the state’s voters approved a Medicaid expansion ballot measure in 2020, and as of October 2021, Medicaid expansion in the state was fully in effect. In the last several years, voters in Maine, Idaho, Nebraska, Utah, Oklahoma, and South Dakota have approved similar ballot measures to expand Medicaid.

More than 17,000 people had already applied for coverage by the time the applications began processing (three months after they were initially slated to begin, due to GOP lawmakers’ attempts to derail the program). And although enrollment initially lagged behind expectations, nearly 312,000 people were enrolled via Missouri’s Medicaid expansion by early 2023. Enrollment in Medicaid expansion in Missouri peaked at a little more than 350,000 in mid-2024, and then dropped during the “unwinding” of the pandemic-era continuous coverage rule (discussed below). By April 2024, there were nearly 334,000 people enrolled in expanded Medicaid in Missouri. 3 And by late June 2024, the number of people enrolled in expanded Medicaid had dropped to under 300,000. 4

Medicaid expansion extends coverage to adults under age 65 with household incomes up to 138% of the poverty level. In 2024, that amounts to $20,782 for a single individual, and $35,631 for a household of three (children were already eligible for Medicaid at higher income levels). 5

The federal government is paying 90% of the cost of Medicaid expansion in Missouri, just as they do in other states that have expanded Medicaid. But since Missouri’s expanded eligibility rules took effect after the American Rescue Plan was enacted, the state also received an increase of 5 percentage points added to its regular federal matching rate for the traditional (non-expansion) Medicaid population, for the the first two years that expansion was in effect (here’s a detailed overview of how this works).

In Missouri, that amounted to $968 million in additional federal funding. Missouri had estimated that the state’s share of the cost of Medicaid expansion would be $156 million in fiscal year 2022, so the additional federal funding stemming from the American Rescue Plan more than offset the state’s costs in the short term (the traditional Medicaid population is larger and more costly to cover than the Medicaid expansion population, which makes the temporary 5 percentage point increase in the federal matching rate particularly valuable to states that newly expand Medicaid).

This guide was created to help you understand the health insurance options available to you and your family in Missouri. An Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace plan is cost-effective for many people.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Missouri.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Missouri as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

If you are under 65 and don’t have Medicare:

The Missouri Department of Social Services also has information about the managed care plans that are available for MO HealthNet members, and how you can go about selecting one.

If you’re 65 or older or have Medicare, you can use this website to apply for Medicaid.

Many Medicare beneficiaries receive help through Medicaid with the cost of Medicare premiums, co-pays, deductibles, and services Medicare doesn’t cover — such as long-term care.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare beneficiaries in Missouri explains these benefits, including Medicare Savings Programs, long-term care benefits, Extra Help, and income guidelines for assistance.

For three years during the COVID pandemic — from March 2020 through March 2023 — states were prohibited from disenrolling anyone from Medicaid. But states could resume disenrollments as early as April 1, 2023, and are required to redetermine eligibility for all Medicaid enrollees during a one-year “unwinding” period that continues into mid-2024 (in many states, this has been extended by at least a few months, and may continue until late 2024). Missouri has an FAQ page about the return to normal Medicaid eligibility redeterminations and renewals.

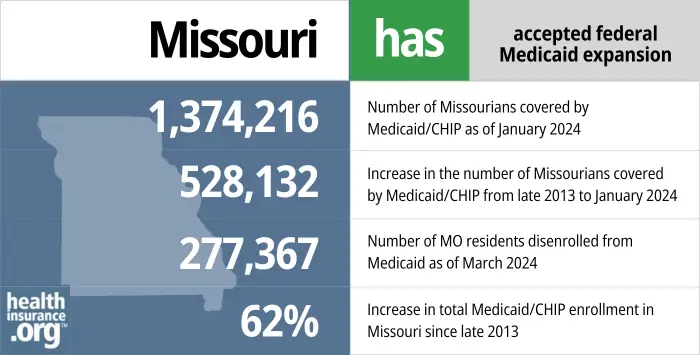

In Missouri, the first round of disenrollments came at the end of June 2023. Missouri expected about 200,000 people to be disenrolled from MO HealthNet, but disenrollments have greatly exceeded expectations. By May 2024, nearly 356,000 people had been disenrolled, while coverage had been renewed for about 856,000 people. 8 As has been the case nationwide, the majority of the disenrollments were “procedural,” meaning the state didn’t have enough information to determine whether the person was still eligible or not.

People who lose their MO HealthNet coverage during the “unwinding” period have had the option to enroll in other coverage at that point. This could be from an employer (if available), Medicare (if eligible), or through the marketplace/exchange (HealthCare.gov). For all three types of coverage, there’s a special enrollment period triggered by the loss of Medicaid. But in general, it’s important to sign up for new coverage as soon as you know that your Medicaid is ending (ie, before the date the Medicaid coverage ends) so that you won’t have a gap in coverage before your new plan starts.

For HealthCare.gov, the special enrollment period continues through November 30, 2024 for people who lose MO HealthNet coverage during the unwinding period. 9 But again, it’s important to enroll as soon as possible, to avoid a gap in coverage.

For the groups described above, only an income limit applies. But for Missouri Medicaid applicants whose eligibility is based on their status as aged (65+), blind, or disabled, there are both income and asset limits. This page is a Missouri-specific overview of how this works.

From late 2013 through early 2024, total enrollment in Missouri Medicaid and CHIP grew by about 60%, to 1,355,155 people.

But enrollment had been even higher in mid-2023, right before the start of the unwinding process. At that point, total MO HealthNet enrollment stood at nearly 1.5 million people. The COVID pandemic played a significant role in driving enrollment higher, in Missouri as well as nationwide. And Medicaid expansion also played a significant role in pushing MO HealthNet enrollment higher, starting in late 2021.

Voters in Missouri approved a Medicaid expansion ballot measure in August 2020 by a margin of about 53 to 47 (the history of the ballot measure is described in detail below). It called for the state to submit a Medicaid expansion state plan amendment to the federal government by March 2021, and for Medicaid expansion to take effect by July 1, 2021.

In keeping with the timeline called for in the ballot measure, the Missouri Department of Social Services (DSS) submitted a proposed Medicaid expansion plan to HHS in February 2021, calling for Medicaid expansion to take effect July 1.

But when state lawmakers passed the 2022 fiscal year budget, they refused to include funding for the state’s portion of the cost of Medicaid expansion. Lawmakers did allocate normal funding for Medicaid (MO HealthNet), but the DSS indicated that it would not change the eligibility criteria for Medicaid coverage, since lawmakers had not expressly allocated funding for that purpose. So the state withdrew the Medicaid expansion state plan amendment that it had submitted to HHS earlier in the year.

A lawsuit ensued, with plaintiffs who would be eligible for Medicaid expansion suing DSS. DSS argued that the ballot initiative itself was unconstitutional, since the state constitution clarifies that ballot measures cannot be used to appropriate state funds. In late June 2021, a circuit court judge ruled that Missouri’s Medicaid expansion ballot measure was unconstitutional because it didn’t include a funding mechanism (it had left that up to lawmakers, as has been the case in other states where Medicaid has been expanded via ballot measure). So Medicaid expansion did not take effect in Missouri on July 1.

The case was appealed, and the Missouri Supreme Court heard oral arguments on July 13, 2021. The following week, the Supreme Court unanimously vacated the lower court’s ruling, and noted that the Medicaid expansion eligibility criteria outlined in Missouri Article IV, Section 36(c) are “now in effect.” That’s the section of the Missouri code that contains the Medicaid expansion language stipulated in the voter-approved ballot measure, including the fact that the new eligibility rules are effective July 1, 2021.

The Supreme Court sent the case back to the Cole County Circuit Court, instructing the court to rule in favor of the plaintiffs and direct the state to expand Medicaid eligibility. That order was issued in August 2021, and the state proceeded with Medicaid expansion as a result. The MO HealthNet website indicated that people eligible for adult Medicaid expansion could submit an application at that point, but that it wouldn’t be processed until at least October 1.

The state noted at that point that the administrative process of expanding Medicaid was expected to take up to 60 days, “due to current staffing capacity and funding restraints,” but clarified that medical costs incurred between the time a person applies and the time their enrollment is processed “may be reimbursed at a later date.” A later FAQ clarified that applications submitted by November 1, 2021 could have coverage backdated to July 1, 2021.

(There is some precedent for this, with the way Medicaid expansion was implemented in Maine in 2019. It was supposed to take effect in July 2018, but was delayed several months due to the governor’s opposition; once it was implemented, coverage was backdated to when people had applied, with retroactive effective dates as far back as July 2018.)

Before MO HealthNet started accepting applications for the newly eligible Medicaid expansion population, the state had very limited Medicaid eligibility for adults. Non-disabled adults without children were not eligible for Medicaid in Missouri regardless of how low their income was, and parents with dependent children were only eligible with incomes that didn’t exceed 22% of the poverty level. Only Texas and Alabama have lower Medicaid eligibility caps, at 18%. There were 127,000 people in the coverage gap in Missouri before Medicaid expansion took effect. They were unable to qualify for Medicaid because the state still had not expanded eligibility for Medicaid coverage, and unable to qualify for premium subsidies in the exchange/marketplace because they earned less than the poverty level. Fortunately, these individuals can now apply for MO HealthNet coverage.

GOP lawmakers in Missouri continued to push back against Medicaid expansion even after it took effect. In February 2022, the Missouri House of Representatives was considering a measure that would have asked voters to weigh in on a constitutional amendment that would make Medicaid expansion subject to annual budget allocations by the state’s legislature. If the measure had gone to the state’s ballot and been approved by voters, GOP lawmakers in Missouri could essentially have unwound Medicaid expansion by continuing to refuse to fund it. Although the measure passed in the Missouri House in 2022, it did not advance in the state Senate.

In states that expand Medicaid, the federal government paid the full cost of expansion through 2016. Starting in 2017, the states gradually started to pay a share of the expansion cost, and states now pay 10% of the cost (the 90/10 split will remain in place going forward). Because of the generous federal funding for Medicaid expansion, states that reject it are missing out on billions of federal dollars that would otherwise be available to provide healthcare in the state.

From 2013 through 2022, Missouri was projected to give up $17.8 billion in federal funding by not expanding Medicaid.

Hospitals in Missouri that treat uninsured patients were especially hard-hit, as their federal disproportionate share hospital funding has started to be phased out (it was supposed to be replaced by Medicaid funding) and the uninsured rate has remained higher than it would have been with Medicaid expansion in place. As a result of Missouri’s decision to opt out of Medicaid expansion, hospitals in the state were projected to lose $6.8 billion between 2013 and 2022.

Fortunately, Medicaid expansion did eventually take effect in Missouri in late 2021. And as described above, Missouri also received additional federal Medicaid funding as a result of the American Rescue Plan and the timing of when the state’s Medicaid expansion took effect.

SB371, introduced in Missouri’s legislature in 2018, called for putting Medicaid expansion on the November 2018 ballot and letting voters decide, but the bill did not advance. A citizen-led effort to get Medicaid expansion on the ballot in Missouri was considered a non-starter in 2018, as it didn’t have the backing of any major groups at that point.

But in 2019, things were different. Healthcare for Missouri picked up the push for a ballot initiative, and received support and funding from The Fairness Project, which helped with the expansion ballot initiatives in other states in recent years.

The ballot initiative was submitted to the state in June 2019, and was approved for the signature-gathering process to begin. Advocates spent the summer determining the feasibility of Medicaid expansion by ballot initiative in Missouri, and announced in September 2019 that they would commit to gathering the 172,000 signatures necessary for the measure to appear on the ballot.

Dozens of petition-signing events took place in communities around the state in the fall of 2019 and early 2020. Although the COVID-19 pandemic put a halt to in-person signature gathering as of March 2020, Healthcare for Missouri announced at that point that they would still be able to submit the necessary number of signatures by the early May deadline, “thanks to a strong and early start to voter signature collections” in 2019.

The signatures had to be submitted by May 3, and Healthcare for Missouri announced on May 1 that nearly 350,000 signatures — almost twice as many as necessary — had been submitted to the Missouri Secretary of State’s office. The Secretary of State certified the signatures a few weeks later, and Governor Mike Parson soon announced that the measure would be on the August 4, 2020 primary ballot, instead of the general election ballot in November.

Parson, who is opposed to Medicaid expansion and the ballot initiative, said that he was placing the measure on the primary ballot in order to give the state more time to implement Medicaid expansion if voters approve it. But supporters of Medicaid expansion, including Parson’s Democratic gubernatorial challenger Nicole Galloway, felt that Parson chose to put the measure on a ballot for a lower turnout election, in hopes that it wouldn’t pass. Oklahoma Medicaid expansion advocates also gathered enough signatures to get an expansion initiative on the ballot in 2020, and Oklahoma’s governor — who is also opposed to Medicaid expansion — also opted to put the ballot initiative on the primary ballot. But voters in both states approved Medicaid expansion, despite the fact that the measures appeared on primary ballots instead of the general election ballots (Oklahoma’s Medicaid expansion took effect July 1, 2021, as scheduled).

Parson made his opposition to Medicaid expansion clear, but he stated that he would “uphold the will of the people” if the Medicaid expansion ballot measure was passed by voters. The Kansas City Star Editorial Board noted in late 2019 that GOP lawmakers in the state could still opt to craft their own version of Medicaid expansion during the 2020 legislative session, incorporating various limitations that could be achieved with an 1115 waiver. But the only Medicaid expansion bills that were introduced in the 2020 session (SB564 and SB603) were introduced by Democrats and did not advance during the session.

A University of Missouri School of Medicine study in 2012 concluded that “Medicaid expansion would be highly beneficial to the Missouri economy and its citizens.” And in June 2014, the Missouri Economic Research and Information Center announced that healthcare job growth in Missouri had slowed considerably since 2012, and was falling behind compared with states that had expanded Medicaid. Healthcare is the state’s largest employment sector.

Former Governor Jay Nixon was a longtime proponent of Medicaid expansion, although the Republican supermajority in the state’s legislature blocked his efforts in 2012 and 2013.

But Senator Ryan Silvey, a Republican from Kansas City, was on board with Medicaid expansion, noting that “it’s going to be damaging to our hospitals if we don’t do something.” Silvey’s Democratic colleagues were also supportive of expansion. The legislature came close to approving a modified version of Medicaid expansion in the spring of 2014, and Silvey noted that some of the lawmakers who opposed it had since retired, meaning there might be a better chance for successful legislation in 2015.

In December 2014, Senator-elect Jill Schupp introduced SB 125, which called for expansion of Medicaid up to 138% of the poverty level, but it did not advance out of committee.

Several other similar bills were introduced during the 2015 session as well, including HB 153, HB 1351, and HB 474. But Republican leadership in the Missouri legislature vowed to block any attempts to expand Medicaid during the 2015 session, and none of the bills advanced to a full vote. Bob Onder, a new state senator from St. Charles, made fighting Obamacare — including Medicaid expansion — his primary focus during the 2015 session. When the Supreme Court upheld the legality of subsidies in states like Missouri that use Healthcare.gov, Onder stated that the Court’s ruling was essentially liberal justices taking the opportunity to “rewrite” the ACA in order to “save” it. There was hope — nationwide — that the Court’s ruling on King v. Burwell to uphold subsidies would galvanize the Medicaid expansion movement, since it indicated — at that time — that the ACA was here to stay. But opposition to Medicaid expansion among Missouri’s legislative leadership remained strong.

Unfortunately, the legislature’s refusal to expand Medicaid meant that hospitals had to cut costs, and in June 2015, Mercy Hospital announced 127 job cuts in Springfield.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.